Sgt. No. 5022: A true war horse story

As birthdays go, it was probably no different to the previous few. It began at sunrise with a mug of muddy coffee or beef tea, perhaps even a biscuit. The day would be spent in the company of friends, many of whom he’d gotten to know exceptionally well. And then of course, there were the war horses, all of whom were under his guard as a soldier serving in the Army Veterinary Corps. (74th Brigade of the Royal Field Artillery, ‘B’ Battery, to be precise.)

As birthdays go, it was probably no different to the previous few. It began at sunrise with a mug of muddy coffee or beef tea, perhaps even a biscuit. The day would be spent in the company of friends, many of whom he’d gotten to know exceptionally well. And then of course, there were the war horses, all of whom were under his guard as a soldier serving in the Army Veterinary Corps. (74th Brigade of the Royal Field Artillery, ‘B’ Battery, to be precise.)

Turning 31 was probably something Sergeant Frederick George Anderson never thought he’d see, grateful as ever to still be alive. His brother-in-law, Private George Holtum never made it to his 21st. He was killed-in-action a year earlier on the battlefield of The Somme, one of the many who fell fighting and whose graves are not known.

As my great-grandfather went to bed on that birthday evening in 1917, he probably did so blissfully unaware that in the morning he would find himself in the middle of one of the seminal events in military history – the Battle of Cambrai, the world’s first ever full-on tank battle. According to a commemorative article in the Telegraph last year, “tanks had been used in battle before, but Cambrai was the first time that they were put to work so mob-handed.”

The battle of Cambrai

Taking place in a woods just outside the sleepy town of Cambrai in north-east France, the Allied objective was always to take the enemy by surprise and advance on a vital supply point on the German Hindenburg Line. The well-established German strategy of occupying high ground meant they were confident of there being no attack from the British. Besides, the trenches were too wide to get across and the horses certainly couldn’t penetrate the ribbons of razor-sharp barbed wire.

It seemed as if it was stalemate. With Christmas closing in, everyone assumed they were in for a long, hard winter.

And then, at 6.20am on the morning of 20th November 1917, the day after Sgt. Anderson’s birthday, the allies executed a spectacular surprise attack on the German lines, overwhelming them with never-seen-before ‘shock-and-awe’ tactics by rolling in over 470 thirty-ton tanks. If you’ve ever watched War Horse, you’ll know the type I mean – huge rearing beasts that gobble up everything in their wake.

One delighted soldier in particular – having seen for the first time what the Mark IV combat tanks could do up close and personal – said, “the enemy wire had been dragged about like old curtains. The tanks appeared to have busted through!”

The ruinous sight must have been terrifying, so much so that thousands of startled German infantry scrambled out of their trenches in the mist at dawn on that chilly November morning. Bewildered soldiers were caught completely off guard. Records show that, according to one German officer:

“At about 9am, retreating infantrymen gave us an account of swarms of tanks – so many that it was impossible to stop them. A little later the tank monsters came creeping to the ridge to the south of the village. Not one of us had seen such a beast before.”

According to German Field Marshall Prince Rupprecht, it was the only time the Allies achieved a complete surprise attack.

A tide of iron

The Germans were quickly overwhelmed. The barrage of tanks crushed through the barbed wire, and by deploying an ingenious technique, they were able to cross the deep trenches with relative ease. The Battle of Cambrai, or the ‘Tide of Iron’ as it was to be known was in full flow. And despite all the new technology, the success of the attack partly came down to the use of good old-fashioned logs. The British had finally worked out how to get the heavy tanks to cross the trenches without falling in or being gobbled up by mud. According to one soldier, George Coppard:

“The tanks – looking like giant toads – became visible against the skyline. Some of the leading tanks carried huge bundles of tightly bound logs and brushwood, which they dropped into the wide German trenches, then crossed over them.”

As simple as it was genius, it also became apparent that the pace of the attack was to be their downfall. So fast were the tanks moving, and so quickly were they dispersing the fleeing German soldiers, it left those British troops at the rear vulnerable to side-on counterattack with no tanks to protect them.

As simple as it was genius, it also became apparent that the pace of the attack was to be their downfall. So fast were the tanks moving, and so quickly were they dispersing the fleeing German soldiers, it left those British troops at the rear vulnerable to side-on counterattack with no tanks to protect them.

One of those would have been my mum’s grandad and his war horses.

As the scattered German troops regrouped, they launched a scathing attack on the British troops at the rear, including the war horses, who by now would be shell-shocked and quivering with fear at the carnage that surrounded them.

As tempted as he may have been to run for shelter, Sergeant Anderson stood firm. He knew that his one and only objective was to stay with the horses to protect them, despite the torrential shelling and carnage. Without the war horses, the officers would not be able to communicate and the heavy artillery would remain abandoned in the 20 inch mud. The advance would be over. The war would be lost.

And all for what?

During the first day alone, the British lost 4,000 of their own men. Fighting was especially fierce around Bourlon Ridge (just before the woods) to the west of Cambrai. The British were squeezed back by German counter-attacks and were left exposed, despite the advancing tanks by now being almost five miles ahead.

Eventually, after a few days the Germans pushed the British back – advancing tanks and all – and by the end of the campaign almost three weeks later, the Allies were all but back where they started. According to official records, the British suffered 47,596 casualties, equivalent to almost 6% of the total number of war losses in just 18 days. The Germans lost a similar amount.

In the time it’s taken you to finish reading this post, the number of deaths on both sides would already have been in double figures. That’s almost one death every 30 seconds. And all, seemingly for nothing.

I can’t begin to comprehend how terrifying it must have been for my great-grandad when he woke up that fateful morning of 20th November 1917. The deafening noise alone would render most folk to jelly. He certainly wouldn’t have known that the war had less than a year to go when he first caught site of those monstrous tanks as they rolled in, guns blazing.

Like his friends that toasted his birthday the night before, their first and only priority was to protect the precious war horses, including the many that were poisoned, shell-shocked, lame, crippled, dead.

Oh, to be able to charge their glasses one final time. Tonight though, only empty chairs and empty tables.

War Horse

As a sergeant in the AVC (the ‘Royal’ would come later when the war ended), my great-grandad would have been one of the 27,000 or so soldiers who looked after and treated the horses. Horses were considered so valuable to the cause that if a soldier’s horse was killed he was required to cut off a hoof and bring it back to his commanding officer to prove that the two had simply not been separated.

At the start of the war, the British Army had 25,000 horses. By time the war ended, in total, around one million horses were sent into battle. Casualties were catastrophic, equivalent to losing one horse for every two men. Only 65,000 horses came back.

Luckily, so too did my great-grandad. I’m not exactly sure when he finally arrived home. War records show that the 74th Brigade went on from the Battle of Cambrai to fight in The Somme and a number of other battles during 1918. On the day of the Armistice they were somewhere near Maubeuge and ordered to the Rhine to cross the German frontier a month later. They remained there for Christmas, before finally beginning to return to England on 20th February 1919. All were home by 29th April, almost six months after the armistice.

I can’t imagine what the scene must have been like as Frederick Anderson arrived back home in Folkestone, a mile or so from where I was to be born some half a century later. His brother-in-law wouldn’t have been with him even though they both lived in the same street. If you’ve ever seen the end of the film or the amazing musical adaptation of Michael Morpurgo’s book, you’ll know what I mean. The scene would have been as sombre as it would have been joyful.

Not forgotten

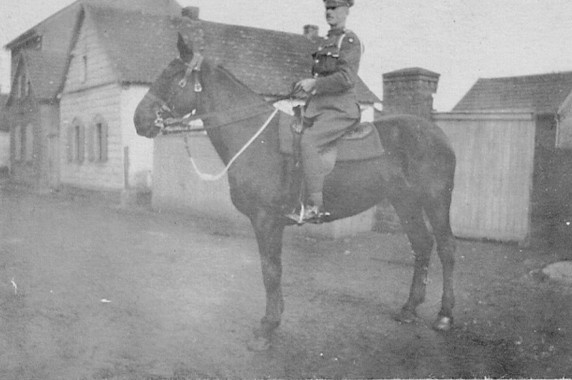

No. 5022 Sgt. F.G. Anderson, R.A.V.C was awarded the Military Medal ‘for exceptional gallantry in remaining with the horses under his charge while under heavy shell fire on 22nd November 1917’. He received his first of a number of medals following church parade outside the church hut at Digbate Camp. It took place on Sunday 25th May 1919 at 10.15am. It would have been a lovely day, as according to met office records the south-east of England was in the grip of a prolonged drought. For my great-granddad, anything but mud.

No. 80038 Pte. G.A. Holtum remains in an unnamed grave and is listed on the register at Thiepval Memorial in the Somme region in France. His name appears alongside 72,336 other young men who also died somewhere in battle and for whom there is no known resting place.

And finally, what of the 476 tanks? Only one survived. Nicknamed ‘Deborah’, she roared into action at 06.20 before shortly being hit by five German shells. She was commandeered by 2nd Lieutenant Frank Heap from Blackpool who skillfully managed to steer the stricken tank into a ditch. Four of the six crew were killed instantly. There the tank remained abandoned for eight decades, buried as landfill some six feet down, until finally unearthed in 1998. Deborah now stands proudly centre-stage and all alone at the centenary memorial museum in Flesquieres, just outside Cambrai.

#ArmisticeDay

With the story over, I feel compelled to try and make a banal comparison to ‘lessons learned in leadership’ or make some other crass or tenuous link. Why else would I write a blog so unlike anything else that I’ve posted before without bringing it round to the usual fodder? Besides, this is a professional account and not one for indulging in family folklore. You don’t subscribe to my blog so that you can read about my relatives, and – quite frankly – why should you?

But today is different, because if it wasn’t for all our great-grandads and mums who sacrificed so much for us all, then there most likely would be no post. Heaven forbid, if the enemy had achieved their objective and killed my great-grandad, I might not even be here now. I hope this post does him justice.

So on a personal note, thank you Sergeant Frederick George Anderson for coming back alive. Above all, thank you to all the thousands of others who were lucky enough to do the same.

To those that did not – just like the horses, Deborah’s crew, George Amos Holtum and thousands of others – this post is for you.

x