Ubuntu: I am, because we are

It has been another extraordinary week. It’s taken the tragic death of George Floyd to make the world sit up and take notice. The images beamed into our homes serve as a stark reminder that as a race, we are far from being united. I thought we had seen the last of this sort of thing, and certainly not in 2020. I was wrong.

We kid ourselves that it is not, but deep-rooted racism is still out there. As teachers, we have always tried to take an anti-racist stand, but evidently that has not been good enough. We need to do more. We have failed.

It’s not easy to sum up the right words when trying to express how abhorrent you find racism. I don’t want to sound pompous or patronising, especially as a white man. Who am I to begin to pretend I understand how it must feel to be judged on the colour of your skin?

To that end, I have been reflecting a lot recently on my trip last year to South Africa. We visited the Langa township on the suburbs of eastern Cape Town and spent time with families and community leaders, as we toured their town and visited their homes.

‘Langa’ means sun in Xhosa and also derives from the name of a local tribal chief imprisoned on Robben Island in 1873. It was a privilege to listen to their stories first hand, and you can feel the real sense of hope that embraces everything that they do.

Langa Township with Table Mountain in the background (author photo).

Langa Township with Table Mountain in the background (author photo).

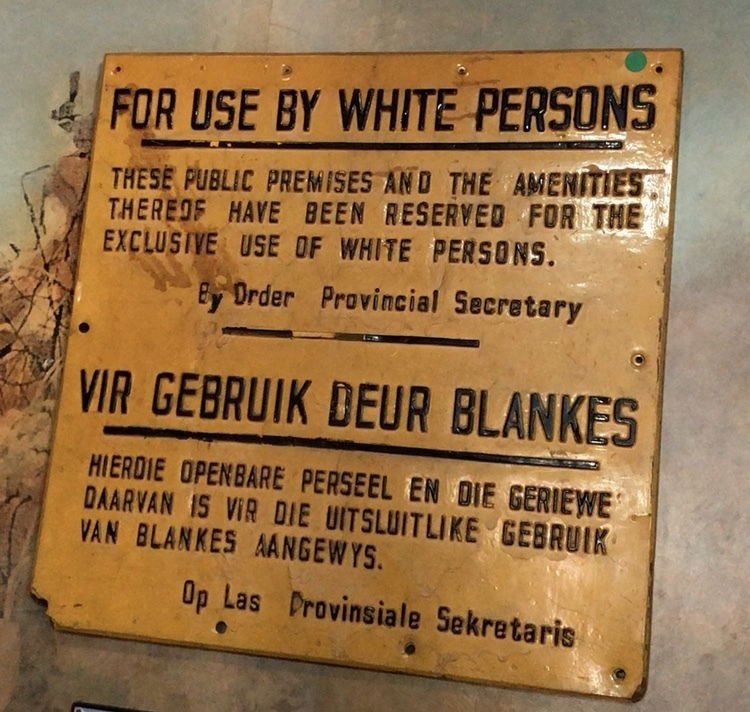

We then went to District 6, a cosmopolitan and affluent area in the heart of the city, shadowed majestically by Table Mountain. It was no different when it was bulldozed in the 1960s by the apartheid government so that they could force the black families out of their homes and into the squalid townships. District 6 was then declared a whites-only area in 1966 under the Group Areas Act.

Over 60,000 people were forcibly removed to the townships in the barren wastelands of the Cape flats, such as Langa. Peaceful protestors were either shot, detained indefinitely, or sent to Robben Island. The District Six museum is a haunting reminder of the brutality of the apartheid regime.

District Six Museum, Cape Town. Note the banner 'No matter where we are, we are here.' (author photo)

District Six Museum, Cape Town. Note the banner 'No matter where we are, we are here.' (author photo)

If you ever get the chance to visit Robben Island, then you must. Nelson Mandela understandably made it famous for being imprisonments there for so long. But there are many other black prisoners whose brave stories of freedom-fighting remain unknown. People like Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, Raymond Mhlaba, Govan Mbeki (his son became President following Mandela), Andrew Mlangeni, Elias Motsoaledi, Robert Sobukwe, Dikgang Moseneke, Sedick Isaacs, Marcus Solomon, Lizo Sitoto and Antony Suze. They should all be household names.

These brave men risked the death sentence in order to make a stand against apartheid and they paid a very heavy price indeed. It is Mandela though that everyone - quite rightly - wants to learn about. To stand outside his cell is as chilling as it is humbling.

Since returning home, I’ve devoured virtually every memoir I could find on the above men. I have had to resort to scouring the secondhand bookshops and eBay, as scandalously the books aren’t commonly available.

One book that really resonated was the one that inspired me to name my new company after. The book is called More than Just a Game: Football v Apartheid. It is a true story that tells how a band of extraordinary men organised themselves as prisoners, and that together they defied all odds to be allowed to play league football in one of the ugliest hellholes on earth.

The men channeled their anger and frustration into an active force in their ongoing struggle against apartheid. For 20 years they played organised football as prisoners, following strict FIFA rules, under the jurisdiction of their self-named Makana Football Association. In 2007, FIFA granted the Makana FA honorary membership of FIFA, the only non-country association to be granted such honour.

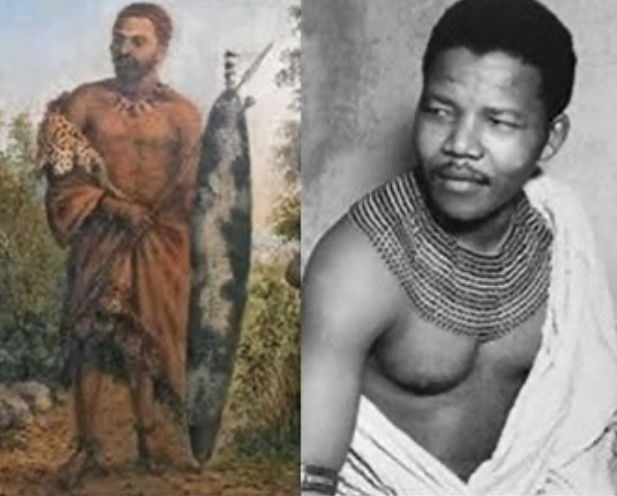

To my eternal shame, I had never heard of the name ‘Makana’, even though it is the name of a mountain in Hawaii (meaning ‘gift’ in Hawaiian). Makana though is very much a real person, and in Xhosa folklore was the original Nelson Mandela, 200 years before him.

Their life stories follow an almost similar trajectory, and there are those who believe Mandela to be some kind of reincarnation. Mandela and his friend Walter Sisulu would often tell stories to fellow prisoners about the legendary spiritual leader of the Xhosa tribe who led his people against British brutality in the early 1800s. Fast forward to 1960, and thousands of others were doing the same. Nothing much had changed

Like Mandela, Makana was imprisoned on Robben Island, and Mandela would often take strength from the presence of Makana’s spirit. Makana drowned off the coast of the prison island when leading an audacious escape. As their leader, he made sure he stayed behind so that all his men got across safely to Bloubergstrand across the bay. When it came to Makana’s turn, he perished, alone. His body was never found. His spirit though remains very much alive.

Makana and Mandela.

Makana and Mandela.

So, by way of contributing in some small and insignificant way to #blacklivesmatter, I’m leaving you with a poem that Africans would sing around the campfire.

It is offered in the spirit of Ubuntu, another Xhosa term, meaning 'humanity', and translates as 'I am, because we are.' It is also a philosophical way of life, based on the belief that there exists a universal bond or life force that connects all humanity through sharing.

Never before do we all need to be more Ubuntu.

The origin of the song is unclear, but is first believed to have been sung in 1980 in Angola, two decades before the ending of apartheid.

It goes like this…

Two centuries before this one

In Africa’s southern lands,

A war was just beginning

That would put blood on many hands.

Every struggle has its heroes

This song is just about one;

Makana of the Xhosa

Who drowned off Bloubergstrand.

Swim Makana, swim Makana, swim

On the shore where we wait

Our children go thin

Come Makana, come Makana, come

I hear you, said Makana

To the voices in his head.

But the water’s growing higher now,

I am as good as dead.

New people will come to lead you

And many will go and die

Before the spirit of Makana

Will at last be home and dry.

(You can read more about the story of Makana, including watching a short YouTube documentary in which the men from the Makana FA tell their story, on the Makana Leadership website.)

Original sign inside District Six museum. These were typical throughout South Africa (author pic).

Original sign inside District Six museum. These were typical throughout South Africa (author pic).