Please Ofsted, stick to your brief

Two particular tweets caught my eye last week. One was from Ofsted and the other a leading academic. The Ofsted one was in relation to them wanting to do some good by conducting research. The other was based on research about how Ofsted do more harm than good. I had to read on.

Let’s deal with the Ofsted tweet first, not least because the timing of its release appears to coincide with their 25 year celebrations at Westminster. Maybe this was deliberate and that they are in an ebullient mood. It may be that they feel the time is right for them to divert from their core purpose and to venture into pastures new. We know that their five-year corporate plan is currently in draft form and so perhaps a bit of kite-flying is inevitable.

As the national independent regulator and watchdog, I was surprised to learn that Ofsted even had a research department. I’d certainly never come across it in my time as an inspector. It was never referred to as part of our ongoing training. For example, it would have been useful to have reviewed and understood the implications of international research on how the process of inspection is flawed. This would have led to an improved framework that was fit-for-purpose for all schools.

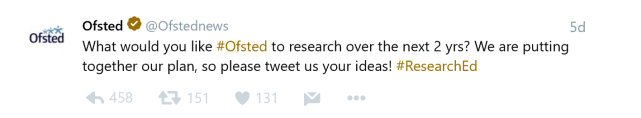

According to Ofsted themselves in a subsequent tweet, the research arm is part of their in-house team. Presumably their budget is such that they now have sufficient time and money to conduct research on behalf of the profession. I assume that it was this team that put out last week’s tweet – apostrophe, hashtag and all:

Ofsted have continued to retweet it on a daily basis and it has since gone on to generate almost 800 replies. They probably wish they had never asked. Suggested research areas include all the usual suspects, such as teacher well-being, retention, governance, SEND, parental engagement, curriculum, ITE, funding, and so on. Perhaps the cheekiest suggestion was this particular tweet: ‘How Ofsted have got away with wasting over £200m a year for 25 years without demonstrating any improvement in education.’ Ofsted need not bother with this one though as the National Audit Office are already on it.

There’s been no response from Ofsted yet as to what their research focus (or foci) will be. Apart from a ‘thanks for all your suggestions’ tweet several days ago, we are going to have to be content with checking our timelines on a daily basis.

Despite a number of you asking the ‘when? why? how?’ questions, Ofsted appear to have made it clear that they want to position themselves as players in the already congested world of #ResearchEd. Maybe this is a good thing and that the regulator is simply trying to modernise the brand and endear itself to the profession. If that’s the case, then I’ve clearly missed the point. I just don’t see that it is the regulator’s job to conduct independent research (not least because they are not independent). Best practice reports, yes, based on what they observe. But research? No.

Take synthetic phonics schemes for example. What if Ofsted were to research their effectiveness and to then come to a conclusion as to which one is best? Does this mean we should all go out and use it? Clearly, Ofsted will be stating a preference which is the one thing they have quite rightly tried to avoid doing. The same can be said of almost anything pedagogical, such as intervention strategies, how to give feedback, questioning and so on.

My fear is that some schools will inevitably end up adopting systems merely to please Ofsted based on their research, rather than what best suits the school. This will simply exacerbate teacher workload to the point of implode, leading even further to criticisms being made of unscrupulous leadership teams.

On a personal note, I must add though that I was particularly pleased to read that the issue I wrote about in my recent TES piece came up a number of times as a suggested theme. I’m not sure it will be selected as it will require Ofsted having to research the negative impact that inspection has on those schools in deprived and challenging areas. Their research will therefore conclude that it is not a level playing field. (The term to be used here is ‘unjust’, an adjective that we shall return to shortly.)

Which brings me nicely to the second tweet that caught my eye last week. This one was reported by the TES, based on a blog from Frank Coffield, Professor of Education no less at the universities of Durham, Newcastle and the London IoE (emeritus). According to the TES, Professor Coffield launched a ‘scathing attack’ on Ofsted based on the very thing that Ofsted purport to want to do; namely research.

In his post he writes for the British Educational Research Association (BERA) and so is well-qualified to have a view. Professor Coffield is adamant that the research-based evidence is compelling. This is a flavour of what he says: ‘The clear balance of the evidence made me conclude … that Ofsted currently does more harm than good.’ And if that wasn’t enough, he goes on to state that not only is their work ‘invalid and unreliable’, it is also ‘unjust’.

The professor goes to some lengths to qualify the adjective, referring to detailed empirical evidence that suggests that over time Ofsted judgements aren’t always equitable to those schools that find themselves in challenging circumstances. A one-size-fits-all framework is therefore not supported by the evidence.

According to Professor Coffield, the research suggests that Ofsted are incorrect to claim that their judgements are fair, valid and reliable. As a result, those of us in schools at the receiving end of an inspection ‘are diverted from looking after students to looking after inspectors’. I suspect that this will be even more so if we feel obliged to pander to Ofsted’s research.

Whether it’s the role of Ofsted to conduct research on our behalf remains to be properly debated. I am firmly against it and would urge a rethink. The fact that so many people responded readilyto Ofsted without questioning it must surely give them encouragement. I appear to be alone on this and so shall forthwith let the matter go.

Instead, I’m going to get myself a copy of Professor Coffield’s new book. It’s all about replacing Ofsted with an alternative model based on a number of key principles, such as trust, growth, support, dialogue and appreciative enquiry. The book is called ‘Will the Leopard Change its Spots?’ I know already that the answer is probably ‘no’. Perhaps Ofsted’s desire to move into research is an implicit acknowledgement that they are indeed attempting to change their stripes. Who knows? I shall though, remain as optimistic as ever for the future – spots, stripes or whatever.

I’ll leave you at this point with one further thought from the professor, that seems, somewhat unintentionally, to serve as a defiant call-to-arms:

‘Ofsted doesn’t belong to the government but to us, and we have a right to call for change.’

So there.

Postscript: 3 hours ago Ofsted tweeted: ‘Thanks to everyone who sent us research ideas: we aren’t taking any more but will consider all suggestions carefully.’