Why we need to evolve at building belonging

Interesting new research has recently been published on 'belongingness' and 'organisational identification'. It's important to know about it because workplace cultures and practices are evolving as schools adapt to new ways of working. In this post, we take a look.

Creating a culture of belonging has long been the gold standard. We know from the research that if staff do not feel included they are less likely to perform as well as they can.

According to the annual Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Report (Ozolins et al, 2021) inclusion is defined as ‘feeling respected, valued, safe, trusted, having a sense of belonging and being able to do your best work.’

Sadly, the report concludes that only 43% of staff feel that they belong mainly because the workplace lacks diversity. This is the average across all staff. It is even lower for disabled employees, minority ethnic staff, and those with a faith other than Christianity. These colleagues feel even less of a connection with the workplace.

The report is based on a survey of 16,000 staff in 380 schools in England, so it paints a pretty sorry picture of the state of play.

It's no different across the globe. According to recent research by McKinsey (De Smet et al, 2021), just over half of staff (51%) cite a lack of belongness as their reason for quitting their job. This is no mere snapshot: this is based on workplaces (education included) in the UK, Australia, Canada, the United States and Singapore.

Solving the problem requires no quick-fix. School cultures and workplace practices have been shaped over decades. ‘No wonder leaders become fatigued: They are uncertain about what to do, and it can be difficult to cut through the noise.’ (Beach and Segars, 2022).

But cut through it they must. So what to do?

Well, one possible solution might be found in a recent research article published last month in the Journal of Management (Weisman et al, 2022). It suggests that leaders need to pay more attention to an individual’s ‘sense of oneness’ and that to do this they need to know about the four major categories (or antecedents) that will help predict belongingness.

This means that in so doing, leaders can adopt a more proactive approach to EDI and purpose-driven culture building, rather than constantly reacting to it by having to address high staff turnover and subsequent recruitment challenges.

By then of course, it’s often too late. It becomes a crisis.

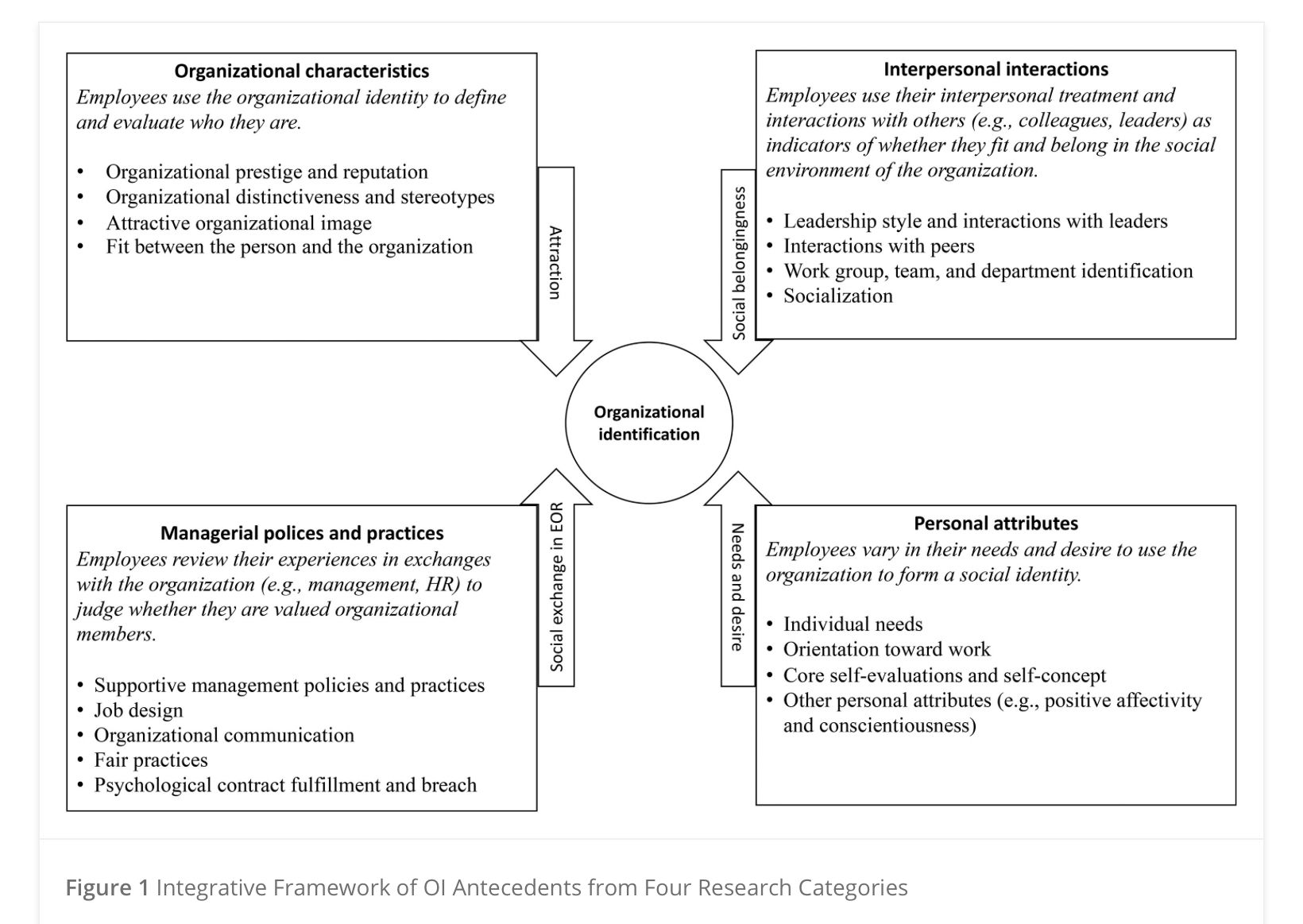

The team of researchers organised the categories into four types (adapted below for schools). Each of these are indicators of organisational identification (OI):

1. Characteristics of the organisation (or Attraction), such as the extent to which the school has built reputational trust through prestige, distinctiveness, USP and whether it has a strong track record of success.

2. Managerial systems and policies (or Social Exchange), such as appraisal, recruitment and reward, CPD, leave, flexible working etc., and the extent to which this values and works in favour of the individual. In short, does the school treat its workforce fairly and equitably?

3. Interpersonal interactions between staff members (or Social Belongingness), such as in a culture of psychological safety where levels of functional fluency are high, and authenticity pervades within a culture of collaboration.

4. Personal attributes of colleagues (or Needs and Desire), such as the commitment from individuals to choose to belong because they believe in the purpose and mission of the school. These in turn appear to drive the collective/social group in a shared direction (vision).

Attraction, social exchange, social belonging, needs and desires: leaders need to know about all four if colleagues are to identify with the school. And by identify, I mean not only that an individual feels that they have a voice in the organisation, but that their voice is similar to others, is listened to, valued, and acted upon.

Leaders might want to spend time thinking about what these are like in their own schools and what it is that they are doing to attend to them.

(Source: Weisman et al, 2022)

As with all new research, more work is needed. In this case, the authors themselves suggest that more attention needs to be given to how the dynamics of identification and belonging change over time. This is especially relevant in a post-pandemic world given the shift in working practices in regard to digital transformation (such as flipping the curriculum) and flexible and remote working patterns.

This suggests that many schools are at a pivotal moment in regard to how they adapt their working practices to respond to the ‘future of work’.

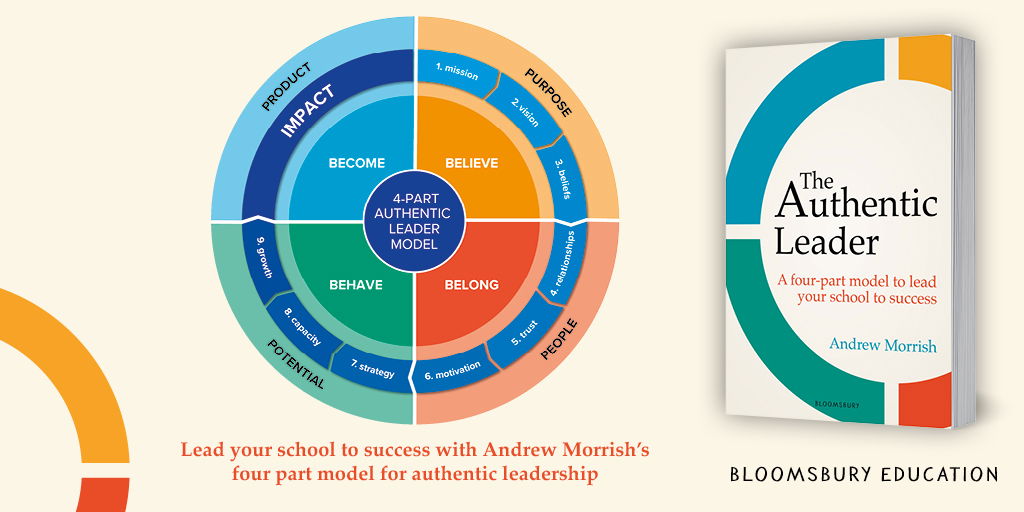

I would suggest that those schools with the strongest cultures will be fine. In other words, those that regularly pay attention to each of the nine baseplates in my latest book, such as trust, relationships, motivation, vision, and growth.

In these schools, the 4 Bs are well established: Believe, Belong, Behave and Become. These are the key Components of a Culture of Authenticity (COCOA).

In schools with well-established cultures (ones that are purpose-driven and ethical), the beliefs of the organisation are deeply embedded. These are the ones that will stand the test of time.

This is because the beliefs have been verified through sustainable periods of success in terms of pupil outcomes, both within and beyond the classroom (Schein, 2004). So embedded are these justifiable beliefs, that they continue to be taught to new members of staff by existing employees almost unknowingly.

They have become habits.

But therein lies the paradox. If schools are to be nimble enough to respond to change, such as the challenges identified by the research above, then perhaps these deeply entrenched cultures will prove to be their downfall if the beliefs are no longer relevant to new ways of working. Their strength unwittingly becomes their very weakness.

We know how hard it can be to unbreak habits. However, if we are able to influence the normative models that we have worked so hard to embed, there is always a way. Perhaps one way of doing this is through the use of Dagan’s (2008) Influence Model.

The influence model works on the assumption that staff make an emotional contract with the school if certain psychologically safe conditions are in place. These include:

- Fostering understanding and conviction. “I understand what is asked of me and it makes sense.”

- Reinforcing with formal mechanisms. “I see that our systems and processes support the changes I am being asked to make.”

- Developing talent and skills. “I have the skills and autonomy to behave in the new way.”

- Role modeling. “I see leaders at all levels and people like me behaving in the new way and so I will too.”

It is important that leaders know how to go about doing this. In may ways, this is how we reculture a school, providing of course it leads to sustainable impact. It helps if my three habits of an authentic leader are evident, and that leaders are constant, consistent and convinced.

I am, however, with James Clear on this (author of Atomic Habits): Habits are ‘the compound interest of self-improvement.’

Any school that is serious therefore at wanting to think deeply about how best to evolve its culture in order to respond to the future of work would do well to place self-improvement front and centre.

Perhaps there is merit therefore in the OI research above, and that it is only by paying more attention to needs, desires and personal attributes, that true belonging exists.

How best to go about this is an entirely different discussion.

You can read more about belongingness in my latest book, The Authentic Leader: A four-part model to lead your school to success. Published by Bloomsbury, October 2022.

NEW! The ideas in this blog are part of a new course that I am running with Mary Myatt in summer. Called the Huh Leadership Lobby, you can find out more here, or join us for a free live webinar to learn more about the course next month.

References:

Beach, A., and Segars, A. (2022), ‘How a values-based approach advances DEI’, in MIT Sloan Review, Magazine, 7th June.

Clear, J. (2018), Atomic Habits. An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones. Random House Business.

Dagan, N., Baz-Sanchez., and Weddle, B. (2020), ‘Driving organizational behaviour changes during a pandemic’, McKinsey and Company, Blog, 6th August. Driving organizational and behavior changes during a pandemic | McKinsey & Company

De Smet, A., Dowling, B., Mugayar-Bulocchi, M., Schaninger, B. (2021), ‘How companies can turn the great resignation into the great attraction’, McKinsey & Company, 8th September. How companies can turn the Great Resignation into the Great Attraction | McKinsey

Ozolins, K., Jackson, I., Caunite-Bluma, D., and Jenavs, E. (2021), Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Among School Staff. Edurio. EDI_Report_Final.pdf (edurio.com)

Schein, E. (2004), Organisational Culture and Leadership. John Willey & Sons.

Weisman, H., Wu, C., Yoshikawa, K., and Lee, H. (2022) Antecedents of Organizational Identification: A Review and Agenda for Future Research, First published 15th December, 2022.